From Scopes to Roles: Real-World First-Party App Patterns with Azure AD

OAuth is a standard for allowing third-party applications to access APIs on

behalf of users. For example, when LinkedIn wants to access your Google

contacts, you—the resource owner—authorize LinkedIn (the client app) via

Google’s authorization server, and LinkedIn receives a token with a specific

scope (e.g., https://www.googleapis.com/auth/contacts.readonly) to access your

data.

Source Code:

The complete source code for this blog post is available on GitHub:

fredyang/azure-ad-first-party-app

But what if you’re building an internal, first-party application for your company, using your own APIs and Azure AD as the authorization server? Let’s explore how authorization and access control differ for first-party apps, and how to implement both scope-based and role-based access control using Azure AD.

Third-Party vs. First-Party Apps

| Aspect | Third-Party App | First-Party App |

|---|---|---|

| App Ownership | External organization | Same organization as API |

| API Ownership | Different from app (external API) | Same as app (internal API) |

| Trust Relationship | Limited trust; app is untrusted by API | Full trust; app and API are trusted |

| Authorization Server | External (e.g., Google, Microsoft) | Internal (Azure AD tenant of organization) |

| User | External User | Internal User |

| User Consent | Required; user grants specific permissions | Often implicit; user trusts internal apps |

In this post, we’ll use an Angular SPA as the client, a Node.js API, and Azure AD for authentication and authorization.

App Requirements

- Users must log in to use the app.

- Staff users can view and create todo items.

- Admin users can do everything staff can, plus delete todo items.

Using 1 Azure AD client all-in-one

To start, we’ll use a single Azure AD app registration for both the SPA and the API. (Later, we’ll discuss splitting them.)

Managing Scopes

In OAuth, a scope defines the specific permissions an application can request to access an API. Because APIs do not inherently trust third-party applications, these apps must explicitly request the scopes they need, and users must grant consent for those permissions.

For a first-party app (an app owned by the same organization as the API), the API inherently trusts the app more than it would a third-party app. In this scenario, acquiring scopes is less about user consent and more about controlling which internal apps can access which APIs and what operations they can perform.

Technically, a first-party app does not always need to request explicit scopes to access the API, since trust is established by ownership and configuration in Azure AD. However, using scopes is still recommended for first-party apps because:

-

Scopes provide an extra layer of security, ensuring that even trusted apps only get the permissions they need. Scopes help with future extensibility, especially if you later introduce more apps or want to limit certain operations.

-

Scopes are required by Azure AD for issuing access tokens with permissions, even for first-party apps.

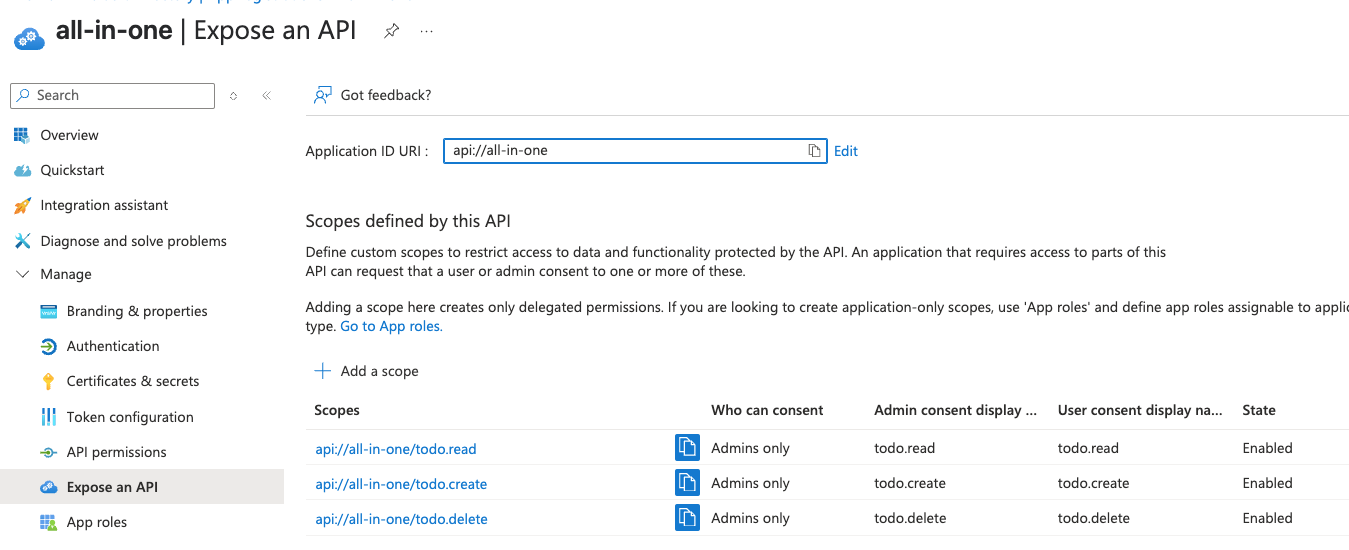

Let’s create three API scopes under the URI api://all-in-one/:

todo.readtodo.create-

todo.delete

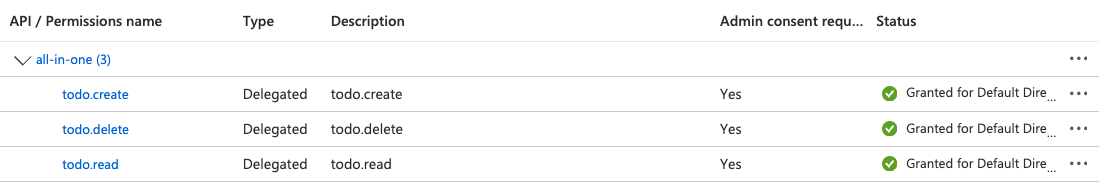

For a third-party app, scopes are usually delegated by a user to the app. As our app is a first-party app, this delegation (consent) is not necessary and even undesired. Azure AD admin needs to grant admin consent to these “Admin only” scopes. After that, they are assigned to the frontend app like the following.

Managing Roles

Roles in Azure AD extend beyond OAuth’s scope concept. While scopes control what an app can do, roles enable fine-grained, user-level access control within your organization.

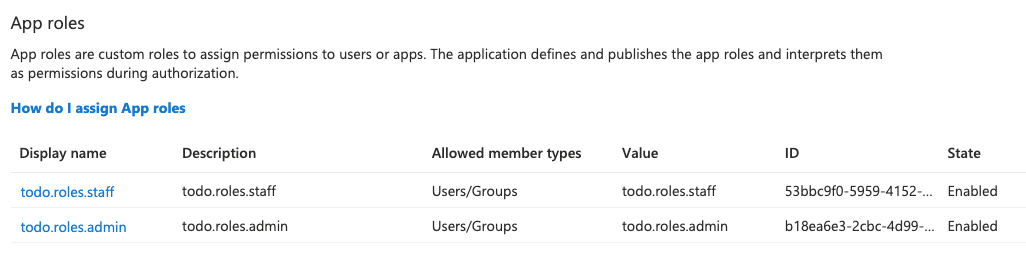

For our app, we define two roles:

todo.roles.admintodo.roles.staff

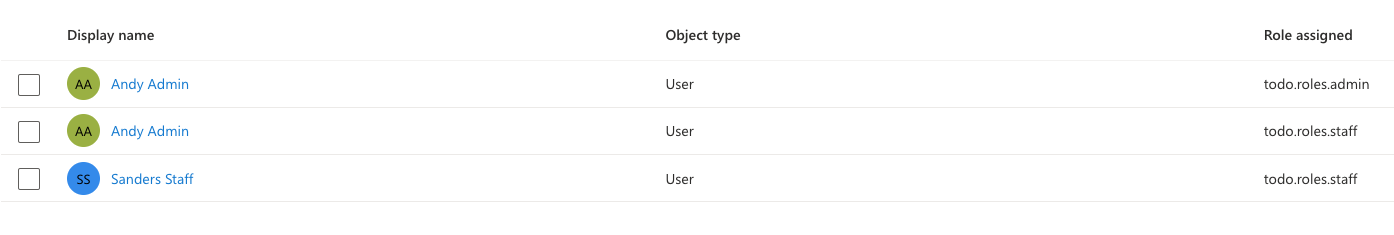

For example, user Admin might have both roles, while Staff has only the staff role.

Configuring the SPA to Call the API

We use MSAL (Microsoft Authentication Library) in the SPA to acquire access tokens with the required scopes:

export const msalInterceptorConfig: MsalInterceptorConfiguration = {

interactionType: interceptorLoginMethod,

protectedResourceMap: new Map([

[

"http://localhost:3000/api/",

[`${environment.applicationIdUri}/.default`],

],

]),

};

The .default scope tells Azure AD to include all permissions assigned to the

app.

Securing the API

The API must:

- Extract and validate the access token.

- Authorize based on scopes.

- Authorize based on roles.

Example middleware:

function hasScope(requiredScope: string): RequestHandler {

return (req: RequestWithAccessToken, res, next) => {

const scopes = req.auth && req.auth.scp ? req.auth.scp.split(" ") : [];

if (scopes.includes(requiredScope)) {

return next();

}

return res.status(403).json({

error: "Scope check failed, client does not have the permission.",

});

};

}

function hasRole(requiredRole: string): RequestHandler {

return (req: RequestWithAccessToken, res, next) => {

const roles = req.auth.roles || [];

if (roles.includes(requiredRole)) {

return next();

}

return res.status(403).json({

error: "Role check failed, user does not have the permission",

});

};

}

export function authorize(

requiredScope: string,

requiredRole: string

): RequestHandler[] {

const rtn: RequestHandler[] = [];

// use CHECK_SCOPE to enable

if (process.env.CHECK_SCOPE === "true") {

rtn.push(hasScope(requiredScope));

}

// use CHECK_ROLE to enable

if (process.env.CHECK_ROLE === "true") {

rtn.push(hasRole(requiredRole));

}

return rtn;

}

Endpoints and their requirements:

| Endpoint | Method | Required Scope | Required Role |

|---|---|---|---|

/api/mytoken |

GET | none | none |

/api/todo |

GET | todo.read |

todo.roles.staff |

/api/todo |

POST | todo.create |

todo.roles.staff |

/api/todo/:id |

DELETE | todo.delete |

todo.roles.admin |

Test for all-in-one client

Let’s run the following command in separate terminals:

# backend

CHECK_SCOPE=true CHECK_ROLE=true \

npx dotenv -e apps/backend/all-in-one.env -- nx run backend:serve

# frontend

# change environment.ts's `useRoleBasedAccessControlOnFrontEnd: false`,

nx run frontend:serve

We can log in with either admin or staff user, and we can check users’ id tokens

and access tokens on the home page. The access token is returned from the

call to endpoint /api/mytoken. Even if we enable both scope check

and role check at the backend, the scope check always succeeds regardless of which user

logs in. This is because the access token’s scp is todo.create todo.delete

todo.read and is assigned to the app, not to the user.

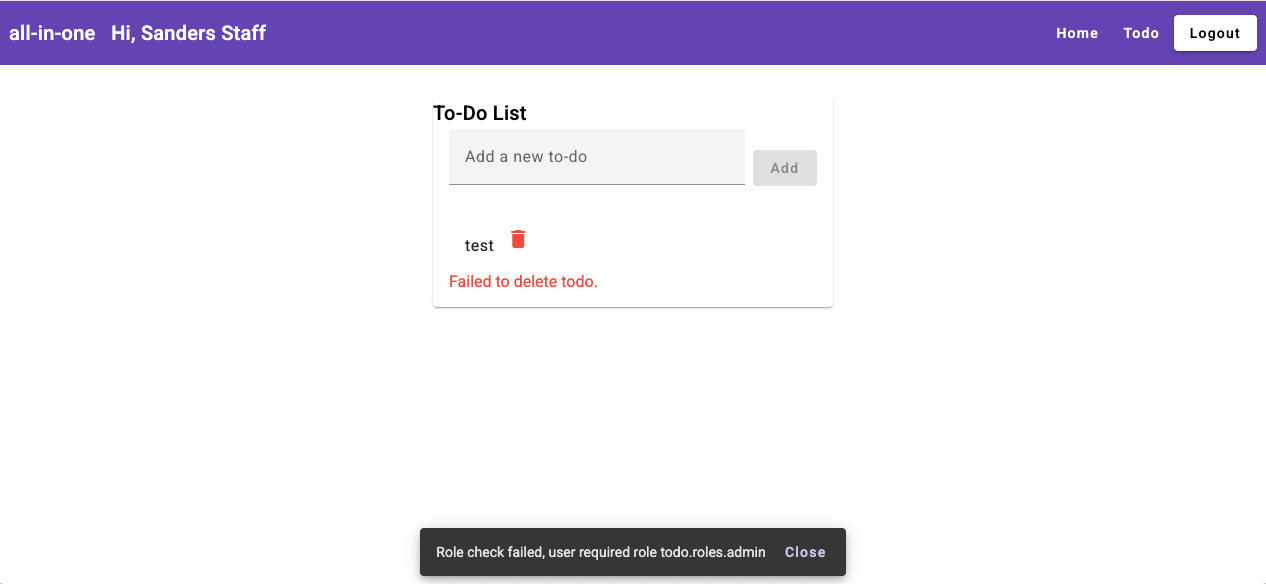

As we started the frontend without role check, the UI looks the same for both staff

user and admin user, but when a staff user tries to delete a todo item, it will

throw a role check error like below.

To prevent this error, we need to enable Role-based Access Control at the

frontend client as well. Because our SPA shared the same client with the API service,

it turns out the Id Tokens also have roles claim. We can use it to show the delete

button only if the user’s role is todo.roles.admin.

hasRole(role: Role): boolean {

const account = this.msalService.instance.getActiveAccount();

if (!account) return false;

const roles = account.idTokenClaims?.roles as string[] | undefined;

return roles ? roles.includes(role) : false;

}

get isAdmin() {

return this.hasRole('todo.roles.admin');

}

<button

mat-icon-button

color="warn"

(click)="deleteTodo(todo.id)"

*ngIf="isAdmin"

>

<mat-icon>delete</mat-icon>

</button>

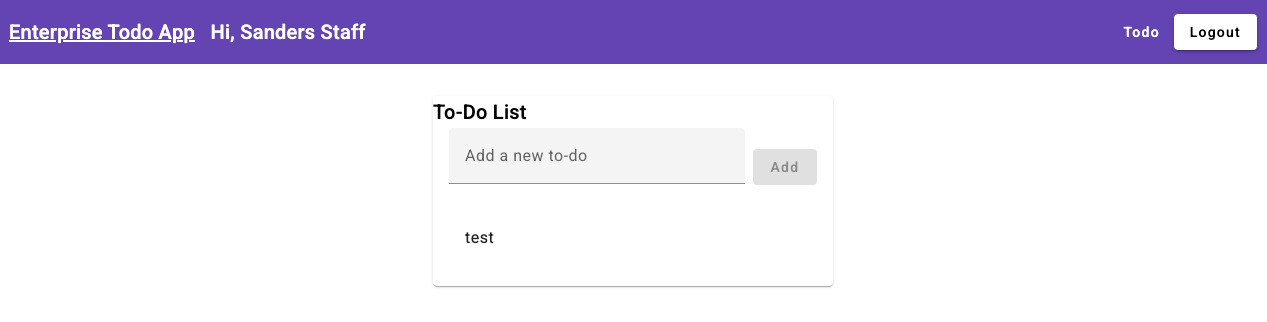

Now change the environment.ts so that useRoleBasedAccessControlOnFrontEnd: true.

The delete button is hidden for the staff user, but it will still be visible

for the admin user.

Using 3 Azure AD clients frontend-admin, frontend-staff, backend

When an API is accessed by only one client application, sharing a single Azure AD app registration for both the client and the API can be sufficient. However, in most real-world scenarios, APIs are consumed by multiple client applications, each with different requirements and responsibilities. To ensure that each client app has only the permissions it needs, you should use scopes to control access. Assigning specific scopes to each client app allows you to grant the minimum necessary permissions, following the principle of least privilege.

So now, let’s create two app registrations (frontend-admin, frontend-staff)

and one app registration backend.

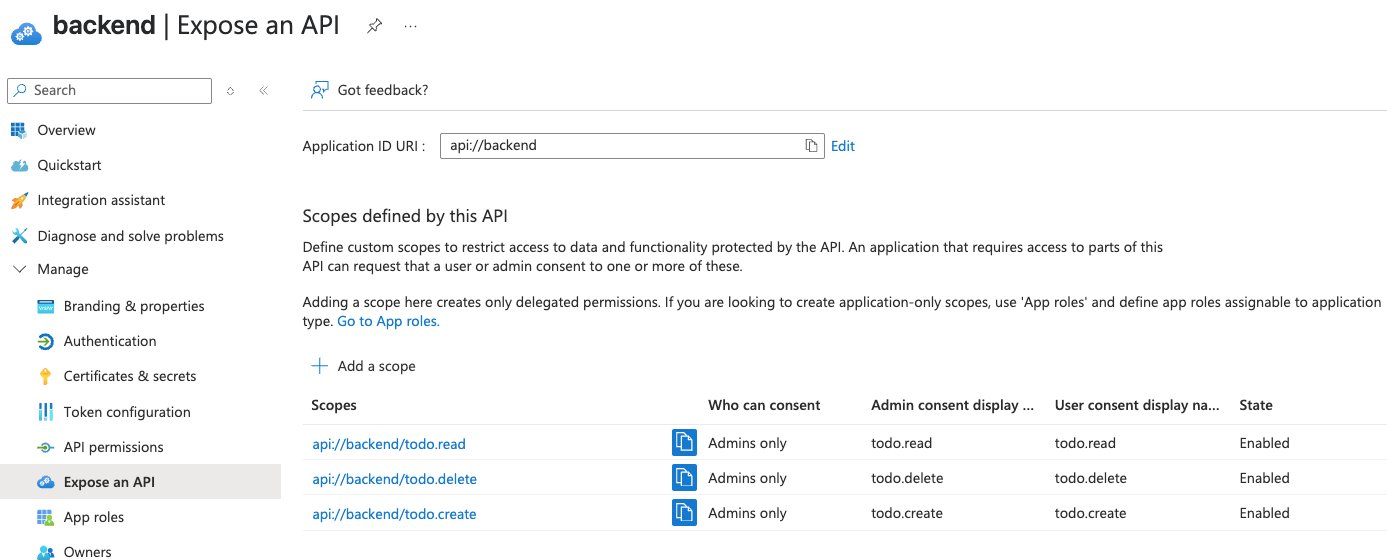

Config backend client

In the backend client, define three “admin only” scopes as before. However, this

time, create the scopes under a new URI: api://backend (instead of the

previous api://all-in-one). For example:

todo.readtodo.createtodo.delete

This ensures the scopes are uniquely associated with the backend API registration.

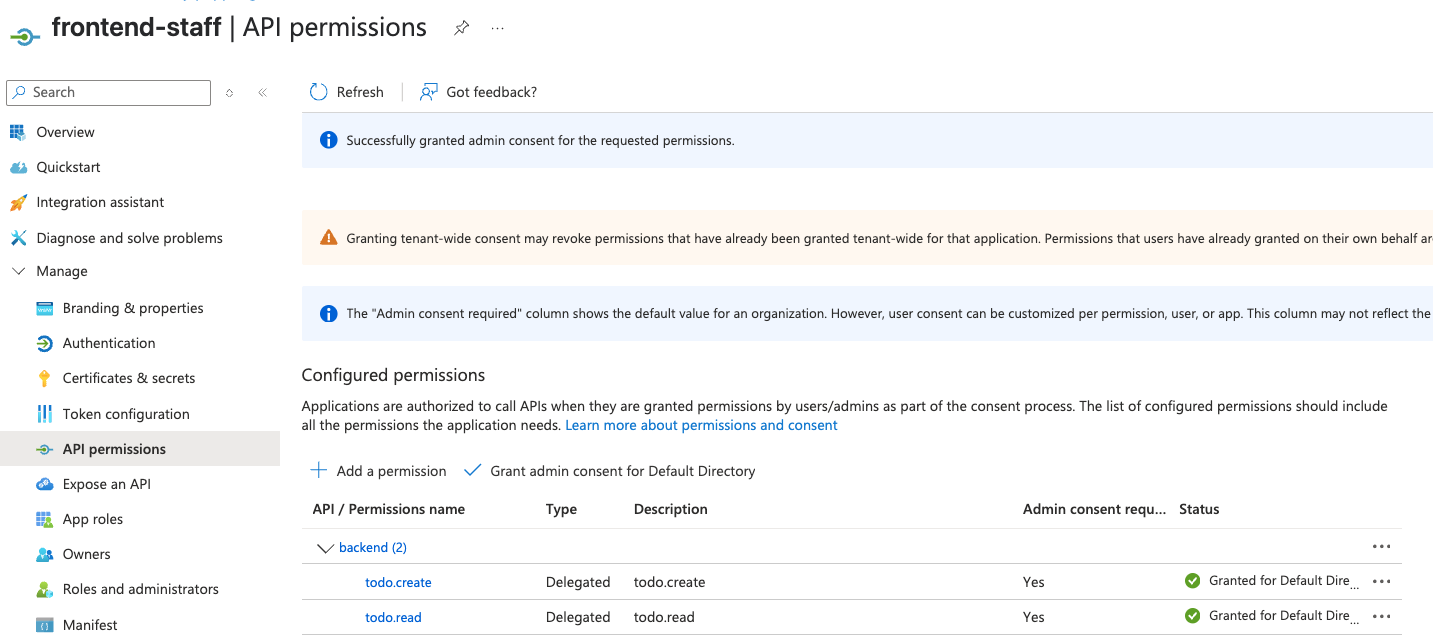

Config frontend-staff

This app is only for staff users, and we can assign todo.read and todo.create

for this app.

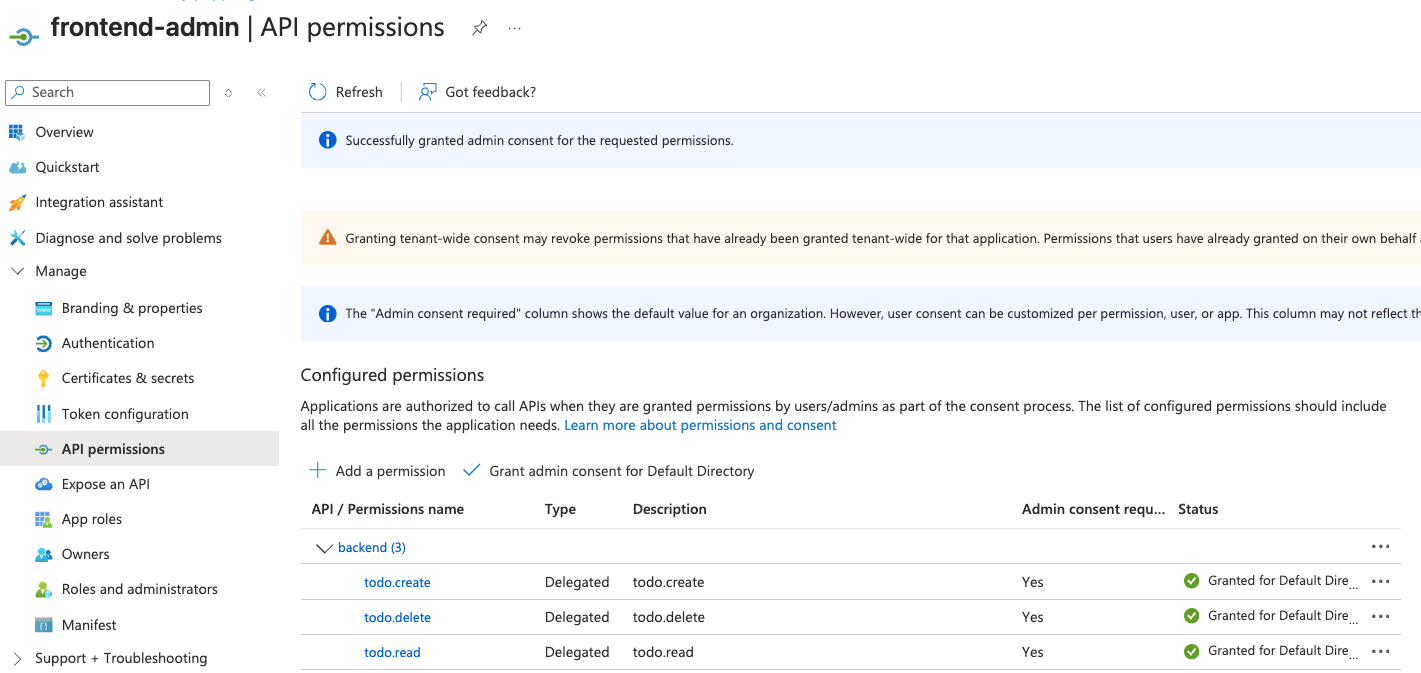

Config frontend-admin

This app is only for admin users. Let’s assign all three scopes to

the frontend-admin client, like the following.

Testing 3 clients mode

In a production environment, it’s best practice to restrict the frontend-staff

client so only users with the staff role can log in, and the frontend-admin

client so only users with the admin role can log in. Each frontend should have

a dedicated UI tailored to its respective user type. However, for testing

purposes, we can allow both clients to be accessed by either user role and use a

shared UI for simplicity.

Let’s run the following code in two terminals:

# backend terminal, disable role checking

CHECK_SCOPE=true CHECK_ROLE=false \

npx dotenv -e apps/backend/backend.env -- nx run backend:serve

# frontend terminal

nx run frontend:serve:frontend-staff

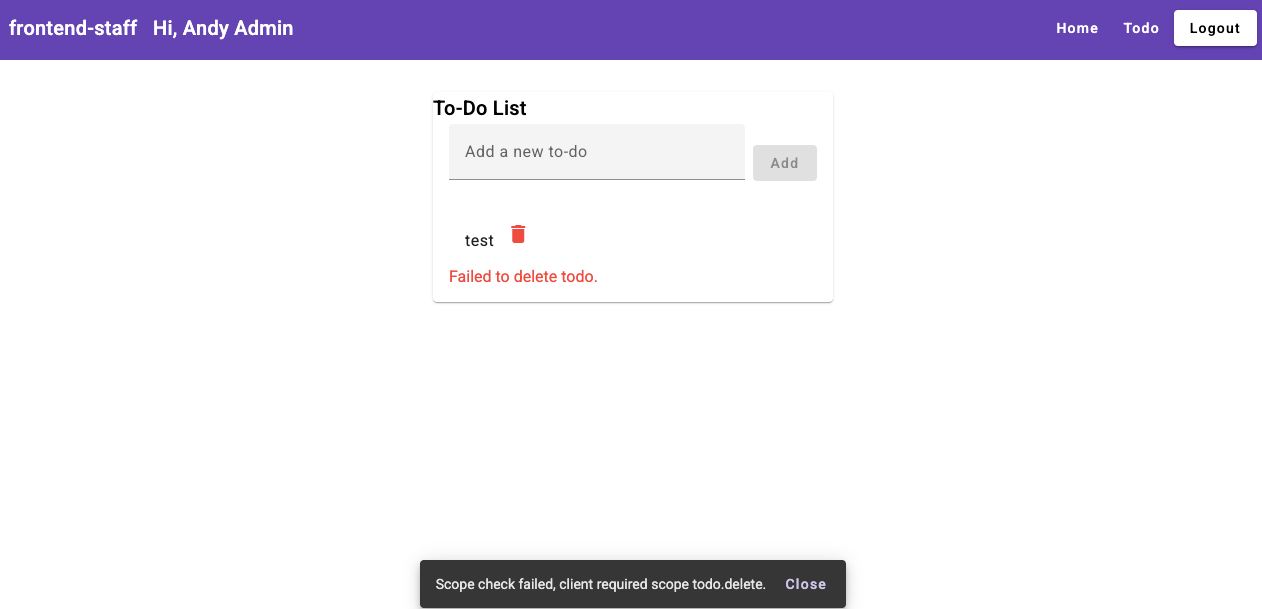

Now, let’s log in as an admin user to the frontend-staff client. The delete

button is still visible—this is expected since role-based checks are disabled in

the UI. However, when attempting to delete a todo item, you’ll encounter an

error: Scope check failed, client required scope todo.delete.

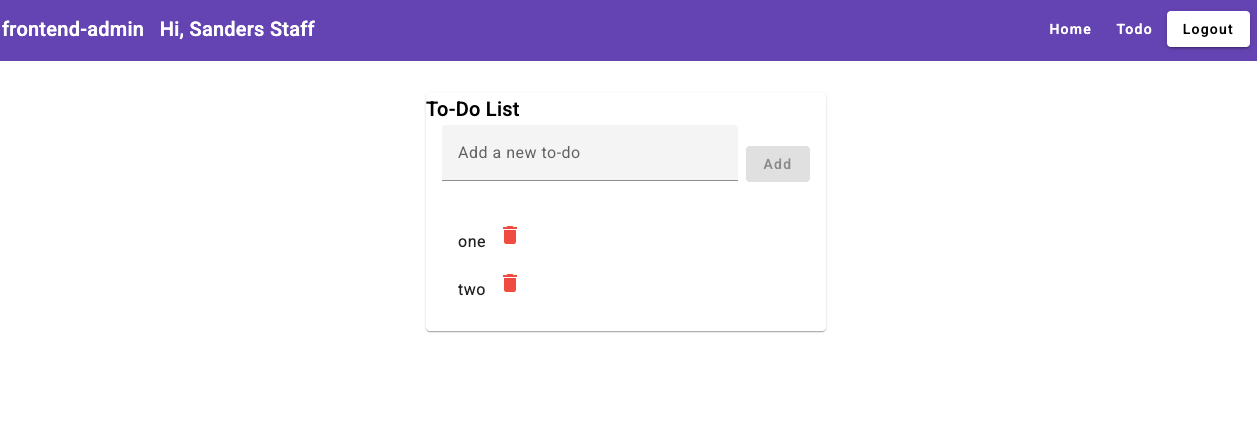

Now, stop the frontend-staff client and start the frontend-admin client. Log

in with a staff user account. Since role checks are disabled on the backend

and the frontend-admin client has the todo.delete scope, the staff user

will be able to delete todo items, even though this action should typically be

restricted to admins.

# frontend terminal

nx run frontend:serve:frontend-admin

The tests above show that Azure AD administrators can assign specific scopes to

each client application, providing coarse-grained permission control. However,

using scopes alone in first-party apps is often not enough—especially when the

UI needs to adapt based on a user’s role. For instance, to hide the delete

button from staff users, the app must know the user’s role. The best practice

for first-party applications is to combine scope-based and role-based

authorization: scopes define what actions an app is allowed to perform, while

roles control what individual users can do within the app. For third-party apps,

scope-based authorization is usually sufficient, since user roles are not

typically exposed or relevant.

Using 2 Azure AD clients frontend and backend

While it’s acceptable to create separate clients for applications with distinct

purposes, splitting highly related frontend apps—like frontend-admin and

frontend-staff—just to enforce only scope-based authorization can introduce

unnecessary complexity in development, deployment, and ongoing management. A

more efficient approach is to use a single frontend client for the app and a

single backend client for the API. By combining scope-based and role-based

access control, you can achieve fine-grained authorization without duplicating

app registrations or increasing operational overhead.

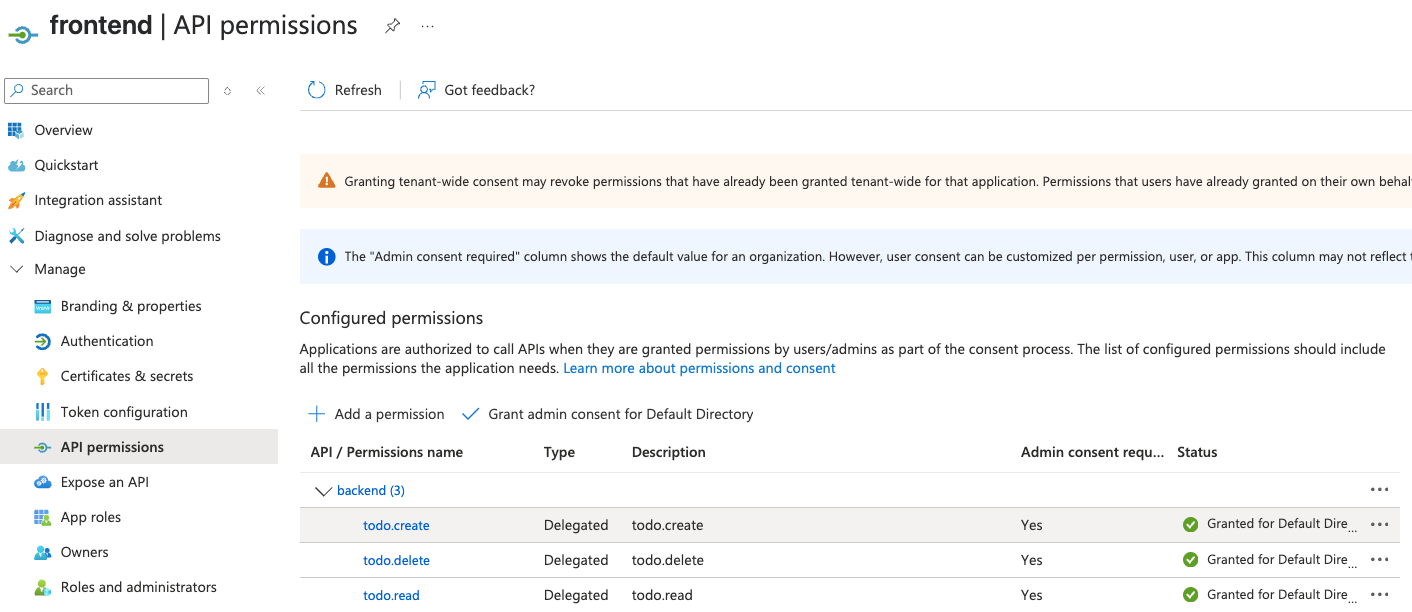

The configuration for this client mirrors that of frontend-admin: it is

assigned all three scopes—todo.read, todo.create, and todo.delete—under

the api://backend URI.

Enabling RBAC in the Frontend When Using Separate Clients

To enable role-based access control (RBAC) in the frontend when using separate

Azure AD clients for the frontend and backend, the frontend app must obtain the

user’s role information. In the all-in-one client setup, role claims are

included in the ID token, so the frontend can access them directly. However,

when the frontend and backend are registered as distinct Azure AD applications,

the frontend’s ID token may not contain the roles defined for the backend API.

While you could duplicate role definitions and assignments in both the frontend

and backend app registrations, this approach adds complexity and can lead to

inconsistencies. A more streamlined solution is to have the frontend request the

access token issued for the backend API, which includes the relevant role

claims. The backend can expose an endpoint (such as /api/mytoken) that returns

the access token or just the user’s roles. The frontend then calls this endpoint

to retrieve the user’s roles and enforce RBAC in the UI accordingly.

Here’s an example of how this can be implemented:

// nodejs backend

app.get("/api/mytoken", (req: RequestWithAccessToken, res) => {

res.json(req.auth);

});

// angular frontend

this.http.get<AccessToken>("http://localhost:3000/api/mytoken").subscribe({

next: (data) => {

this.accessToken = data;

},

});

Testing 2 clients setup

# backend terminal

CHECK_SCOPE=true CHECK_ROLE=true \

npx dotenv -e apps/backend/backend.env -- nx run backend:serve

# frontend terminal

nx run frontend:serve:frontend

With this configuration, the frontend application can dynamically adjust its

UI based on the user’s roles, while the backend API enforces both scope-based

and role-based authorization. This approach ensures that users only see and can

perform actions permitted by their assigned roles, and that API access is

further restricted by the scopes granted to the client application.

Conclusion

When building first-party apps and APIs with Azure AD:

- Scopes are essential for controlling app-level permissions, especially when multiple client apps exist.

- Roles are crucial for user-level, fine-grained authorization and UI customization.

- For third-party apps, scopes are usually sufficient; for first-party apps, combine scopes and roles for robust security and flexibility.

This approach ensures your internal applications are both secure and user-friendly, leveraging the full power of Azure AD.